A coup is underway in Bogota, Colombia. Or so the Colombian president Gustavo Petro claims.

On October 8, Petro took to social media to denounce what he alleges is an ongoing attempt to overthrow his government. “The coup has begun,” he wrote on his X profile.

Petro’s accusation came after Colombia’s National Electoral Council (CNE) announced it was set to launch an investigation into the financing of his 2022 presidential campaign over alleged breaches of spending limits.

Experts say the strong rhetoric is the latest evidence that Petro is struggling to maintain control midway through his four-year term, as a string of scandals threatens to overshadow Colombia’s first-ever left-wing presidency.

The president has denied the accusations, labelling them instead as an attempt by his political enemies to manipulate the CNE to oust him from power.

“The jurisdiction of the President of the Republic of Colombia has been broken. Today, the first step of a coup against me as constitutional president has been taken. If carried out, this act would represent the greatest affront to our democracy in the history of the country,” Petro said in a speech shared on social media on October 8.

Petro, a former guerrilla and Colombia’s first ever leftist leader, described the CNE as “an administrative authority captured by the opposition which seeks at all costs to cast doubt on my integrity”, and added that the entity had “formulated charges” against him. As a result of the CNE’s decision to investigate him, Petro has urged his supporters to take to the streets to denounce the alleged coup.

Opposition leaders dismissed the president’s claims and pointed out that the CNE is within its constitutional rights to probe potential financial misconduct.

Notably, the last two presidents of Colombia, conservatives Ivan Duque and Juan Manuel Santos, faced similar investigations from the CNE during their time in office, as did the centrist Ernesto Samper in the late 1990s.

Focused on politicking

Petro’s claims of a coup have stirred debate in Colombia’s already fraught political landscape and shed light on the strength and stability – or lack thereof – of Petro’s administration.

The president’s strategy carries risks. By framing institutional checks as political attacks, Petro risks alienating moderate supporters and deepening the divide between his administration and other branches of government.

“Petro is digging his own grave, and against all advice he insists on keeping digging. For Petro, there is no middle ground. Anyone that isn’t digging with him is facilitating a coup,” Sergio Guzman, a political analyst and director of the Colombia Risk Analysis consultancy group, told Al Jazeera.

Petro came to power in August 2022, propelled by the Colombian electorate’s demand for political change.

His election marked a political shift in a country that has historically shunned leftist political movements due to their perceived association with Colombia’s decades-long internal armed conflict.

He has vowed to dismantle inequality and implement a series of social, economic, labour and political reforms during his tenure – which the administration has so far struggled to carry out.

Guzman lays part of the blame for Petro’s stalled agenda on his adversarial political relationship with rival political groups.

“The government seems to be much more focused on politicking, so the underlying problem there is that the government has ended up without any other plan that isn’t putting the blame on the opposition and on this soft coup for its own bad management,” Guzman explained.

The CNE’s investigation is by no means a death sentence for the Petro government, as the CNE itself cannot remove the president from office. Should the investigation uncover significant campaign finance violations, the case could be referred to the Commission of Accusations in Congress, opening the door to legal and political consequences, ranging from fines to a trial.

“Colombia’s Commission of Accusations has never convicted any president in history. I am not so convinced that this will result in absolutely anything,” Guzman added.

Tumultuous tenure

Petro’s claim of a coup, whether a political manoeuver or a genuine fear, is the latest chapter in an administration defined by ambition and adversity.

The president is no stranger to controversy. Since assuming power, the Colombian president has seen his tenure mired in scandals and political crises.

In January, his son Nicolas Petro was indicted on charges of money laundering following his arrest last summer. His son admitted to receiving money from drug traffickers intended to fund his father’s campaign along the country’s Caribbean coast.

Nicolas stated that his father was unaware of the payments.

In addition, leaked audio last year appeared to capture a member of Petro’s administration threatening to release damning information about his election financing. The scandal resulted in two dismissals: that of his then-chief of staff and the ambassador to Venezuela.

It was a symptom of wider turmoil within the Petro administration. Petro has frequently reshuffled his cabinet, swapping out key figures on three separate occasions.

That amounts to 38 different ministers in just over two years in a cabinet containing 19 ministerial seats. By contrast, his predecessor, Ivan Duque, appointed 40 different ministers during his four-year term.

Petro has also struggled to deliver on central elements of his agenda. One of his most prominent pledges has been to bring “total peace” to Colombia by ending its six-decade-long internal conflict.

But many of the negotiations he has pursued with armed groups have failed amid broken ceasefires and continuing violence.

Meanwhile, he has struggled to rally support for his legislation in Congress. While able to push through reforms for pensions and taxes, other reforms, like his healthcare plan, have stalled amid opposition.

“What this all illustrates is just how out of steam this government is and how little room for manoeuvre it really has. No one really takes it seriously any more,” Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin America studies at the US-based Council on Foreign Relations, told Al Jazeera.

Nonetheless, Petro’s approval rating has remained constant, oscillating around the 30 percent mark for several months, despite his administration’s obstacles.

Guzman and Freeman admit Petro still faces an uphill battle to deliver on his legislative agenda. This is due to the scale of his ambitions and the recurring political complications the administration has faced thus far.

Freeman added that Petro is likely to “spend the rest of his term pretty ineffectively”.

A difficult path forward

Guzman added that the president’s tendency to generate controversy and discredit much of the criticism levelled at him had impacted his credibility both domestically and overseas.

“The situation has gone from concern to mockery for some international observers, and this is serious because it somewhat reduces the legitimacy of the accusations made by the president,” he said.

But Petro’s administration has attempted to cast doubt on the legitimacy of his most recent scandal.

Speaking on a local radio station, Blu Radio, one of Petro’s lawyers, Hector Carvajal, said that the president’s defence would not recognise the CNE’s accusations, arguing that they lie outside Colombia’s legal framework.

Still, Carvajal emphasised the seriousness of the proceedings.

“It is serious that a fine should be imposed on the president of the Republic because a precedent of this nature cannot be set in the country,” Carvajal said.

Many of Petro’s supporters also believe that the accusations against the president have been exaggerated.

“In comparison to previous governments, the [scandals] aren’t even comparable,” Robinson Duarte, an economist who voted for Petro in 2022, told Al Jazeera. He argued that the accusations were part of a smear campaign.

“The main point of highlighting them is to equate the governments in order to tell people not to have hope in democracy because politicians are all the same and they all steal. When that idea prevails, people stop participating. They stop believing.”

Colombia’s political future under Petro remains uncertain. While the president still enjoys support from key sectors, particularly among marginalised communities and leftist groups, some experts question his ability to govern effectively.

“It is difficult for Petro’s government to achieve everything he promised. It is also hard to govern as the institutions are already built and mainly occupied by people who are close to the opposition,” Duarte said.

“Perhaps Petro didn’t realise how difficult it was going to be to govern, and hence the difficulty in being able to deliver.”

Related News

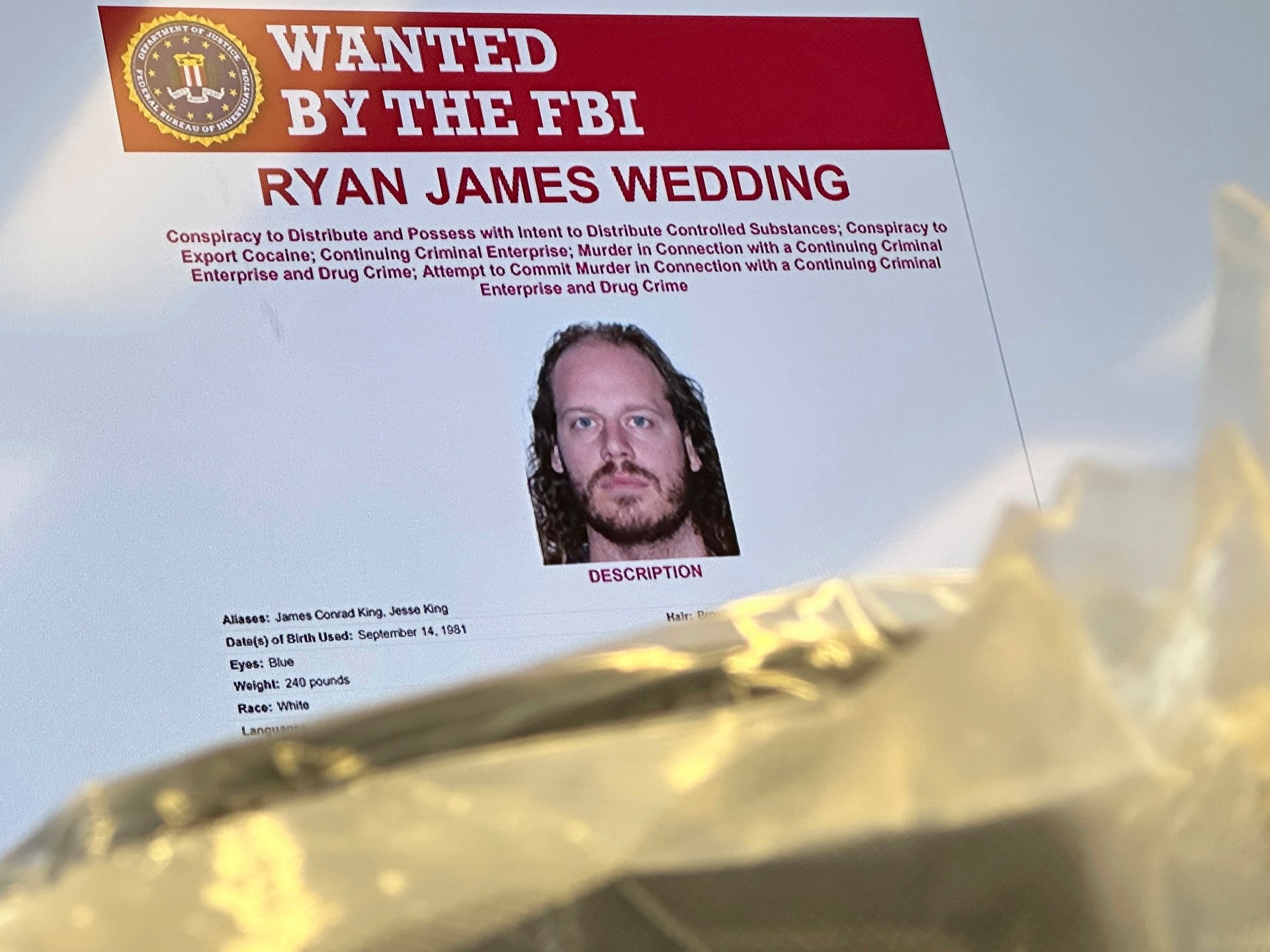

Former Canadian Olympian charged in major US cocaine-smuggling case

China says two citizens killed, one injured, in Pakistan ‘terrorist attack’

What caused the devastating floods in Nepal?